Nick Rockel

April 23, 2020

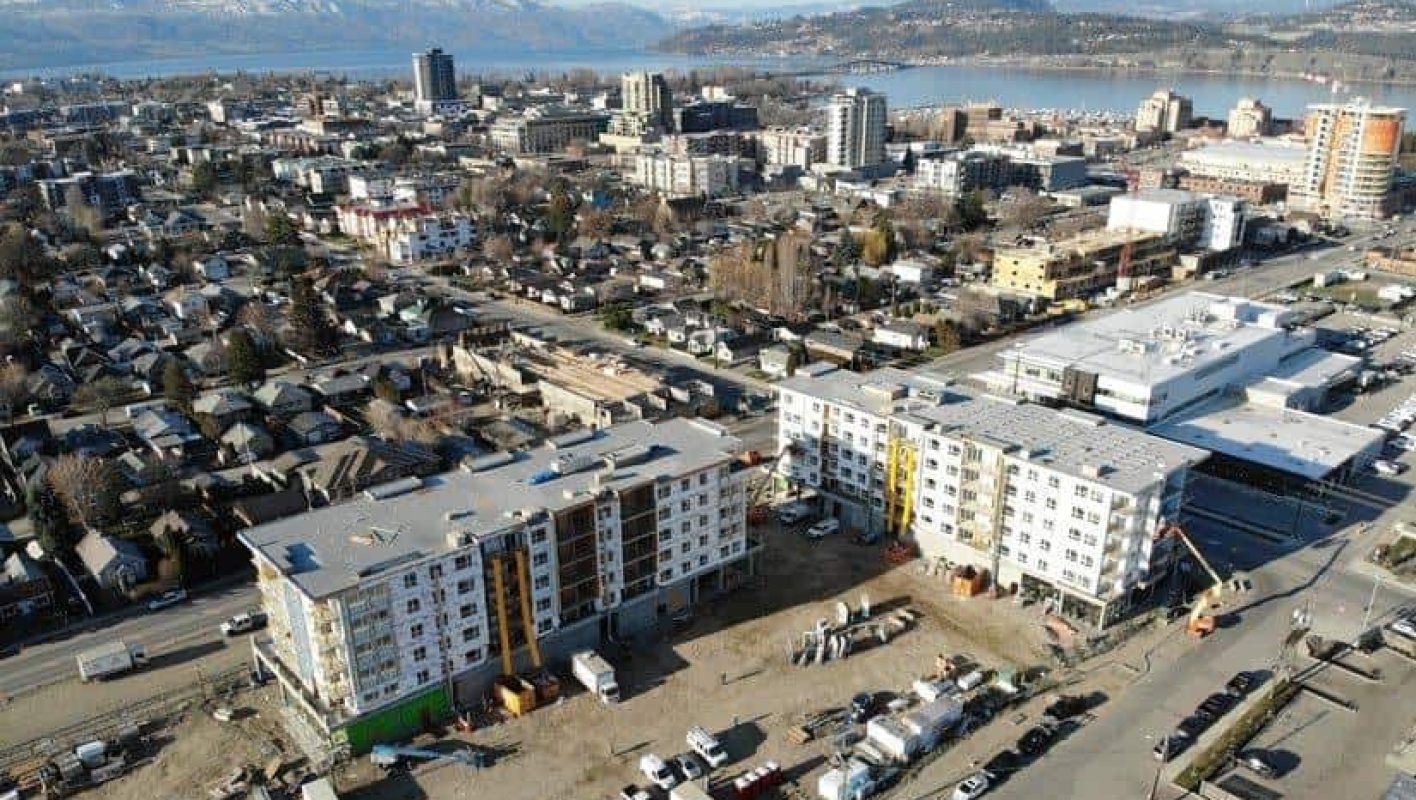

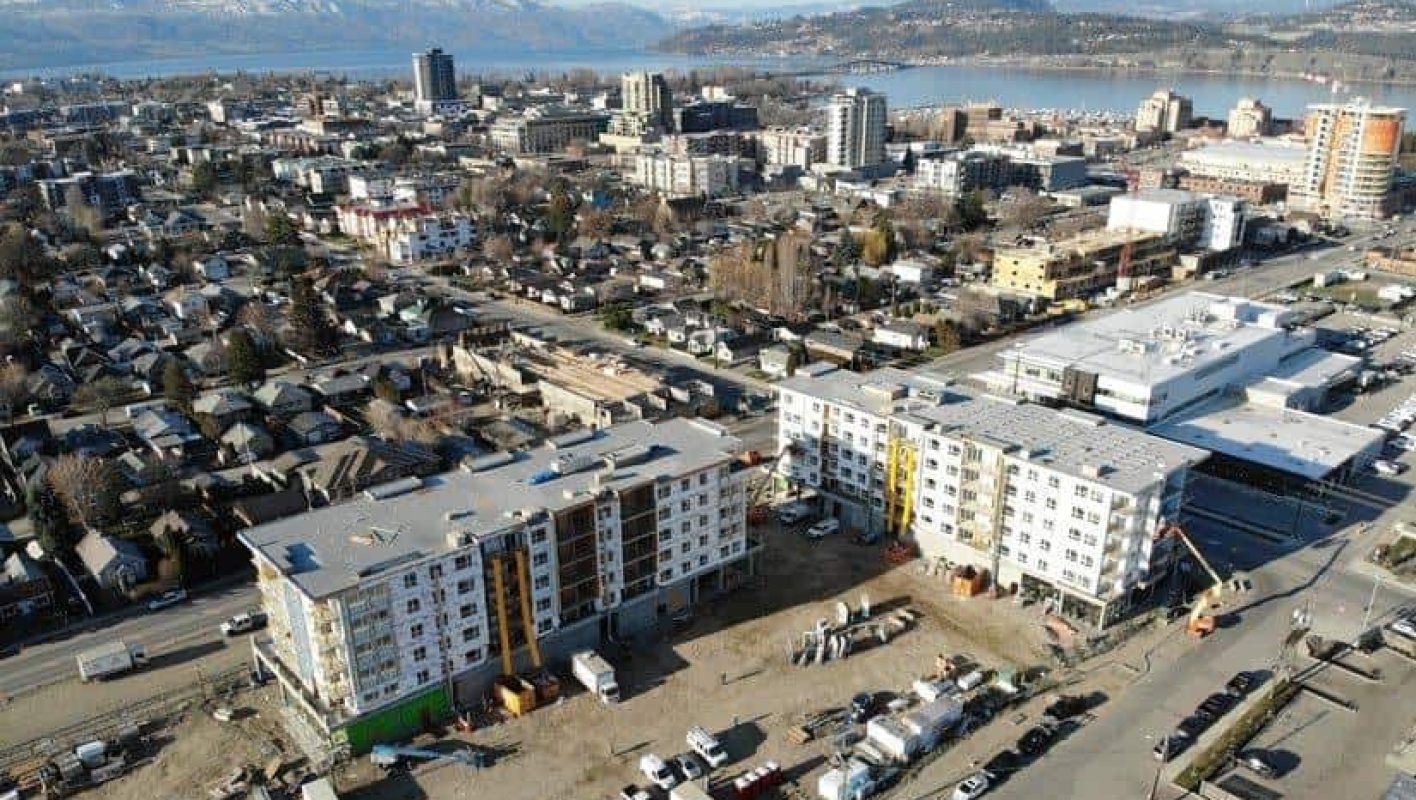

The Lodges, a Kelowna residential development, is one of six projects that Vancouver-based PC Urban Properties Corp. has under construction in B.C.

Although industry players remain confident, the pandemic poses challenges for the property market. It also raises questions about the province’s overall economic resilience

So far, besides ushering in a certain remoteness, the COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t changed much for PC Urban Properties Corp. Everyone at the Vancouver-based real estate developer is still employed, and the 20-member team has spent the past several weeks adjusting to working from home. “I think everybody’s getting a little bit grumpy,” says principal and CEO Brent Sawchyn. “There’s a real desire to get this behind us and let’s get back to the office, let’s keep doing all the things we were doing.”

PC Urban, whose portfolio spans residential, office, retail and industrial properties, has six projects under construction. They include two multifamily buildings in Kelowna and Port Moody, for a total of 400 units; a 23-unit townhome complex in North Vancouver; and three IntraUrban light industrial developments. “We’re fortunate in B.C. that construction has been declared an essential service, so all of those projects continue to move forward,” says Sawchyn, adding that PC Urban plans to start two more in May.

For him and the rest of the provincial real estate industry, the question is what an unprecedented event like COVID-19 will do to demand and supply. Although some asset classes might weather the pandemic better than others, there’s consensus that the longer it drags on, the tougher the recovery will be. And looking beyond real estate, this crisis has exposed some uncomfortable truths about how resilient B.C. is to economic shocks.

For April, PC Urban’s projects are cash-flowing, Sawchyn says. “The vast, vast majority have paid their rent, which is great. And people are closing on units like they committed to.” On the other hand, there are two office projects that the company has identified to start construction in 2021. “We’re being a little bit more guarded about what those will be like,” Sawchyn says. Post-COVID, homebound workers might be keen to return to traditional offices, he notes. “But a formal place of business may encompass a larger footprint because people need more space. People don’t want be on top of each other.”

As the pandemic struck B.C. in March, residential real estate was showing more signs of life after a speculation tax and other measures cooled the market last year. At some 6,700 units, sales grew more than 17 percent compared to the same month in 2019, according to the British Columbia Real Estate Association (BCREA). The upswing was especially strong in Metro Vancouver, where sales surged almost 47 percent year-over-year.

The average MLS residential price gained 12.6 percent during the first quarter, reaching $763,031. Sales dollar volume shot up some 37 percent year-over-year, to $12.9 billion.

You’ll have to wait for the April numbers, but everything points toward a meltdown. “It was looking good from a real estate ownership perspective, affordability being the big concern,” says Elton Ash, regional executive vice-president at Re/Max of Western Canada. “Then COVID hits, and the market pretty much stops except for people who had sold and needed to buy.”

Then again, property values are holding steady—for now. “I think the big story is the absence of big price drops so far,” says Tom Davidoff, a UBC Sauder School of Business economist whose research interests include housing. Although some buyers might have gotten bargains, Davidoff notes, “to my knowledge, we haven’t seen a mass cut in pricing for transactions. And so the interesting question is how long that can persist.”

With the residential market losing both buyers and sellers, the longer the crisis lasts, some people will be forced to sell, Davidoff says. “I don’t see how this goes for a year and house prices aren’t affected.”

Summer is the new spring market

Andrew Hasman, a realtor on Vancouver’s west side, watched business drop off in March. “We were heading into what I would consider to be almost, in some segments, tight market conditions where supply was low, demand was high,” Hasman says. Most of the activity surrounded properties selling for $2.5 million or less—deemed affordable in this part of town—whose prices were starting to edge upward. “That looked to have come to a grinding halt.”

As well as fewer buyers, Hasman has seen a substantial decline in listings. “People just didn’t want to have strangers coming in their homes, for obvious reasons,” he says. “So supply has dropped, demand has dropped, and the market feels like it’s going into a bit of a pause while we try to figure out how we’re going to live our lives during this very unusual period of time.”

For realtors, that adjustment includes offering virtual tours to prospective buyers. “If they need to see the property, we can get them in there, taking extra precautions,” Hasman says before putting a positive spin on things. “It’s kind of a good time to buy again, because now you’re not going to be in multiple bids with a whole slew of other buyers.”

Re/Max’s Ash knows of two homes that recently sold virtually, without the buyers paying a visit. “It’s indication of how, because of this crisis, the consumer experience is going to change with the way that realtors present properties.”

Virtual tours aside, foreign buyers will be out of the picture for some time. “It’s going to be a very localized market until people can get back on a plane and start travelling,” Hasman says.

The realtor is cautiously optimistic that if B.C. keeps bending the curve of the outbreak and loosens physical distancing, sales might pick up in a few months. “We could see a spring-type market emerge mid-late summer as people want to get out and finally get on with their decisions to buy and sell.”

Ash says Re/Max, headquartered in Denver, is keen to see the April sales numbers. “We’re all adjusting our business plans because especially as a franchisor, our royalties are split between a fixed fee and percentage of volume.”

But he remains sanguine about the B.C. market. “This economic and real estate slowdown isn’t a result, especially in British Columbia, of financial issues or lack of consumer confidence,” Ash says. “We’re anticipating that once we get through this and reach a more normal semblance of life, there’ll be a fairly quick windup, subject to, of course, the elephant south of the border.”

1978 all over again?

Data on how COVID-19 has impacted the B.C. real estate market may be scarce, but there’s little doubt that risk is growing. Although the Bank of Canada has cut its overnight lending rate to 0.25 percent, some observers expect banks to raise interest rates because people could find themselves unable to pay their mortgages and rent.

Urban planner Andy Yan, director of the City Program at SFU, thinks the pandemic has exposed Vancouver’s economic fragility. Besides real estate, Yan explains, the economy is driven by service industries such as tourism, which has been clobbered by COVID-19. Not only do tourists help fuel short-term rentals like Airbnb, but many long-term renters work in tourism and hospitality. “If you were either counting on Airbnb or on a renter living in your secondary suite helping pay for your mortgage, and now they can’t, what do you do?” Yan asks.

Add in the fact that international travel is now very difficult, and things could get much uglier. “You have the local economy not doing well, and now you’re cut off from the global economy,” Yan says. “So it feels like it’s 1978,” when Metro Vancouver resembled what he calls Detroit by the Pacific. His summary of that era: “It wasn’t good.”

When it comes to retail and office real estate, the future looks uncertain, too, Yan reckons. It’s easy to blame Amazon, but storefront retail was already struggling before the crisis, he says. “You know how COVID takes out people with pre-existing health conditions? Well, we have pre-existing economic conditions.”

As for the office property market, Yan says that before people started staying home, 20 to 30 percent of Metro Vancouver’s labour force already worked there. “If you accelerate that and it goes into now 40 or 45, maybe even 50, how much are they going to stay at home?”

Bryan Yu, deputy chief economist with Central 1 Credit Union, also sees uncertainty ahead. “Commercial is probably a little bit problematic, especially the retail side, and even for some of the commercial product as work from home becomes much more normalized,” he says. “Will companies go back to requiring that large footprint they have now, or are they moving to a more nimble, work-from-home type of environment?”

Either way, creating a new local economy won’t be easy. Given what the pandemic has revealed about the risks of relying on global supply chains, one possible scenario is that manufacturing returns to the region. But as Yan points out, the City of Vancouver converted much of its industrial land to residential in the 1980s and ’90s. “Now where does that industrial perhaps go?” he asks. “It either goes to, say, Surrey or Abbotsford, or it goes to Calgary or Winnipeg.”

For the province as a whole, the fact that tourism, retail and other service industries dominate spells trouble in a deglobalized world, Yan warns. In food service alone, more than 120,000 B.C. workers have lost their jobs, at least temporarily, Restaurants Canada estimates. “There are these green shoots in technology or highly specialized manufacturing, but they can’t generate a mass of employment,” Yan says.

A different kind of recession

As the old investment disclaimer goes, past performance is no guarantee of future results. But in a recent report, the B.C. Real Estate Association offers what it calls preliminary projections on how COVID-19 could affect home sales and prices during the next 24 months. With the province now unofficially in a recession, the study looks at how three previous ones—1981-82, 1990-92 and 2008-09—impacted its housing market.

“We get a pretty sharp decline in the original months, and then things bottom out four to six months in the future and start to recover,” says chief economist Brendon Ogmundson. “And by the next year, we usually have a pretty vigorous recovery of home sales.” After those earlier recessions, home sales rebounded by 24 to 46 percent.

This time around, the BCREA forecasts that sales will fall 30 to 40 percent in April and stay depressed for the summer. As physical distancing and other steps to control the virus gradually relax, it expects pent-up demand and low interest rates to bring homebuyers back. By early 2021, the BCREA projects, sales will return to a baseline annual pace of 85,000 units.

But the unusual nature of the COVID-19 recession complicates matters, Ogmundson admits. “The timing part is the real difficulty because we don’t know when things are going to be back to normal.”

Assuming a return to some semblance of business as usual, the housing market should firm up relatively quickly, Central 1’s Yu wagers. “People are still going to be looking for homes,” he says. “It’s really a question of how much damage has been done by the economy to people’s household incomes, where the equity markets are and how low interest rates are going to be.”

In B.C. and across the country, what kind of risk do high levels of consumer debt pose to housing and the recovery? During the fourth quarter of last year, the average Canadian household owed $1.76 for every dollar of disposable income, according to Statistics Canada.

“It’s a vulnerability that didn’t exist in some of the past recessions,” Ogmundson says. “But I think a lot of the measures being taken by policy-makers are going to help steer us away from that kind of tail risk.” Besides income support from government, he cites mortgage deferrals by banks.

So far, Ogmundson reasons, property owners have been spared the worst effects of the crisis. “A lot of the initial job losses tend to be in services sectors where you find maybe younger people and a lot of renters, especially in the bigger cities,” he says. “So it may not be falling as hard—right now, anyway—on homeowners.”

The key will be containing the destruction to just a few months and keeping many service sector workers attached to their jobs through wage subsidies and other supports, Ogmundson maintains. “The real risk is that this goes on a really long time, and so businesses fail, and we don’t get those jobs back.”

Looking further ahead, Ogmundson thinks the province will enjoy strong demand for housing, especially as millennials start families over the next five to 10 years. “When we look longer-term, the B.C. housing market has a lot of things pushing demand.”

Industrial strength

Like everyone else in the real estate business, Chris MacCauley is short on data. “I get asked daily, what’s the impact, what’s the price implication, what’s the discount because of COVID?” says the Vancouver-based senior vice-president with real estate services firm CBRE Group, who specializes in industrial property. “There’s just not enough data points to assess and say, OK, it’s had an impact of 10 percent, 15 percent.”

That creates obstacles for anyone seeking financing, which hinges on an appraisal. “To get an appraisal, you need data points,” MacCauley says. “We’re lagging here by about three months to quantify what the impact of COVID has been.”

But if you happen to own some of Metro Vancouver’s scarce industrial land, MacCauley sees reason for optimism. “The overwhelming sentiment through the U.S. and Canada is that industrial is going to be the bright spot throughout all of this, the sector that’s going to be the most resilient and the one that’s poised for a significant amount of growth.”

First, MacCauley points to the recent spike in e-commerce. Food has been the biggest gainer, with consumers expected to keep buying groceries online after the crisis, he says. “So e-commerce out of necessity throughout this pandemic is going to accelerate that on the industrial side going forward.”

Second, businesses want to change their supply chains. “We’ve learned through this that relying so much on offshore has been problematic, causing significant delays,” MacCauley says. “It’s brought to life some of our supply chain issues, so to prevent that in the future, I think you’re going to see a lot of occupiers looking to significantly grow their Canadian footprint.”

Partly because the economy will be soft, Central 1’s Yu doesn’t expect to see big changes right away. “My view is that for the most part, the economic supply chains are going to remain relatively similar to what they were prior to COVID-19,” he says. “It’s going to take some time for these major shifts to occur.”

Another bonus for industrial property: Metro Vancouver went into the pandemic with a vacancy rate of 1.1 percent, an all-time low. “So we are in a really good position to weather this storm,” MacCauley says. “Even in a worst-case scenario, which we’re not predicting, vacancy is still only 2.2 percent, which is not even a balanced market.”

CBRE expects safety measures to slow down new construction, but MacCauley notes that more than 60 percent of the region’s projected supply of industrial land for 2020 has already been preleased and presold. “By the time we start rebounding and getting out of this pandemic, the uptick will continue to happen,” he says, adding that CBRE is still doing deals. “The taps haven’t been turned off by any means.”

For those reasons and others, MacCauley remains upbeat. “B.C. has done such a great job managing this crisis that there’s a lot more positivity here from the real estate community and from the finance community than there is in other markets,” he says. “We think that on industrial, there will be little to no impact coming out of this.”

Although PC Urban’s Sawchyn admits to some trepidation, he shares that bullishness. “Our health-care system, at this point, anyway, doesn’t appear to be overtaxed, and we have an incredibly strong and fiscally responsible banking system.” he says. “If we get through this over the next six months to a year, I think Canada only becomes a further shining light for investment and business, compared to what you’re seeing south of the border.”

With an eye to opportunities, Sawchyn also believes it’s a good time for all levels of government to put people to work building multifamily rental housing.

“I think generally in the real estate industry, you need to be optimistic,” he says. “You definitely need to be a cup-half-full person, or you’re not going to survive very long.”

Original post